The evolution of a revolution:

The story of the Chicago imagists

by Pamela Bagozinski and Gerard Brown

With names that sounded more like trippy 60's albums than art movements, the artists who comprised the Hairy Who, Nonplussed Some, and False Image shows at the Hyde Park Art Center from 1966 to 1969 started a strange and as yet unsettled dialogue with the art world. With work which still gets lumped into discussions of everything from Pop to outsider art, these artists developed a fresh style that paradoxically defies the limitations of a set definition. So what is Chicago Imagism? You might walk out of "Jumpin' Back Flash" scratching your head in continued wonder at this question. First the facts. The term was reportedly coined by critic Franz Schulze after a handful of loosely affiliated�but temperamentally sympathetic�artists organized groundbreaking independent exhibits at the Hyde Park Art Center under the guidance of its director Don Baum. Critic Dennis Adrian calls Imagism "an amalgam or compound mixture rather than a homogeneous phenomenon of style and ideology." Adrian goes on to note the artists' shared interest in "inner awareness, personal concerns [and] probing one's own personal and artistic issues."

back to top

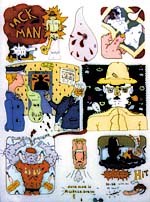

Jim Nutt: "Backman" , 1965

Imagism was important from the moment it hit the ground. Schulze, in a review published in 1967, praised the appearance of what later became called Imagism as "a late season bombshell and sound argument that Chicago painting was alive again, after several indifferent years." A 1969 show at the MCA cemented the young artists' reputations and by 1973, the work had caught on so completely that the Smithsonian's Walter Hopps sent Chicago artists' paintings to the Sao Paolo Biennial and the exhibit "Made in Chicago" was making a national tour. The six artists in the Hairy Who got things rolling in February, 1966. James Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum were all in their twenties and coping with an art world that offered a seemingly dizzying array of influences and ideas. Sarah Canright, Ed Flood, Robert Guinan, Ed Paschke and Richard Wetzel began showing together under the banner of the Nonplussed Some in 1968. The False Image, another group consisting of Roger Brown, Eleanor Dube, Phillip Hanson and Christina Ramberg, put together two shows in 1968 and 1969. Even given Adrian's overarching analysis of the Imagists' broad concerns, how do you reconcile work that runs the gamut from Roger Brown's restraint to Christina Ramberg's striking images of women's accoutrements? While Ed Paschke dealt with more politically charged images (i.e. Lee Harvey Oswald and Confederate Flags), Phil Hanson dealt with tender images mixed with a sense of foreboding. His "candy boxes" have a certain feeling of romance at the prospect of love. They are a gift, but with such a gift, also comes the opportunity for loss, and indeed, he admits, "They have a funereal quality." But overall, throughout the work of many of these artists, there is this evident obsession with the layering of images, of overlap, that is clearly derivative of surrealism, among other things. Just like the original Hyde Park Art Center exhibits, "Jumpin' Back Flash" continues to blur boundaries and fuel discussion. Much of the writing about Imagism you come across tries to shove it into a some sort of stylistic box. Were the Imagist artists reacting to Abstract Expressionism? Appropriating outsider art? Were they just a bunch of ruthlessly careerist art students out to attract attention with flamboyant paintings? It was none of that and more. "The city didn't have a lot of venues for young artists," Philip Hanson recalled when he visited the show with F editor Pam Bagdzinski. Hanson remembers the overshadowing ubiquity of abstract art and how Pop�which was getting big everywhere�seemed like an attractive alternative. Popular imagery represented "a kind of language we could speak through," Hanson says. But not the same as the cool, ironic "mainstream" pop of Roy Lichtenstein or Andy Warhol. Chicago's artists were drawn to the humor and peculiarity of Pop and so-called "low" cultural images that they felt they could speak honestly through. Still, Hanson stresses that Imagism was not simply a reaction to abstraction. Early Imagists were following a trajectory of personal (and more than slightly unfashionable) interests which included Surrealism, collage, and, after 1968, the work of self-taught artists like Joseph Yokum. (Later critics have tried to tie outsider art to the genesis of this movement, but Hanson stresses they were not exposed to it until after the Hyde Park shows were already happening.) Moreover, with many of the artists not yet out of school, they found themselves responding to more immediate influences from teachers and peers. SAIC teachers Ray Yoshida, Ted Halkin and Whitney Halsted were interested and supportive of the young artists. Yoshida's interest in "trash treasures" found in Chicago's Maxwell Street market was probably as influential as any "fine art" the Imagists saw. Despite its early acclaim, Imagism encountered opposition from the start. Hanson recalls hostile crits in which his work was derided as "all clich�s" and the whole Hyde Park Art Center being reduced to a "scene." Artists and institutions were threatened by the Imagists, who they accused of wiping out Chicago's abstract art and distracting attention from "real art." "We were just excited about what we were doing and really had no idea we'd get any attention," Hanson says. Though the groups which organized the early Imagist shows long ago disbanded, many of the individual artists have moved on to singular and successful careers in Chicago and elsewhere. "Everybody went their separate ways," says Hanson, "and nobody likes to be characterized." But being out there as a group, at the start of the careers was definitely beneficial. No one was going to get a one-person show, so a collective was the only option. According to Hanson, "Being seen as an artist is helpful," and showing a few times at HPAC and later at the Phyllis Kind Gallery was important. Since then, both Eleanor Dube and Jim Falconer moved to New York. Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum and Gladys Nilsson have remained connected to SAIC as faculty, and Hanson is still closely connected with Don Baum. Ed Paschke has had a lively career as a painter and is now an SAIC trustee. Ed Flood, Christina Ramberg and Roger Brown have all passed away. The Imagists' legacy is as peculiar as their origin. They have not left a herd of paint-alike student clones, though many of the artists went into academic careers. And while many teachers at SAIC were taught while the Imagist movement was happening and to them it's an inherent part of their history, today's students know little about this important breakthrough in Chicago art. The show at the Cultural Center will hopefully change that. To put the overall effect of the Imagists into context is a difficult thing. How is it still relevant now, if at all? Hanson admitted its very difficult to tell. "Evaluating is very hard, if its your stuff, [and] its thirty years from it." Perhaps we are still too close to the Imagists to evaluate their legacy, if we should even evaluate it at all. "Jumpin' Back Flash" presents an era of history very close to us, one that we should be able to learn from. Perhaps the Imagists have yet to define their legacy with today's artists. For Hanson, the show is a success in that it captures the "energy of a moment." "It was lively," recalls Hanson on his visit to the Cultural Center. "It's all history, but it's an interesting moment that still has a kick to it."

|