Holy Art

Zounds

Hyde Park Art Center

Through April 19

Zounds takes its name from the contraction of the oath "God's wounds." The show itself is concerned with wounds and wounding and "asks why the separation of flesh from flesh may at the same time bind people together in a fascinated, if often troubling experience of witnessing." The show includes the work of Chicago artists Teresa Mucha and Michael Hernandez de Luna, and SAIC student Mariano Chavez (who currently has a show in the Lounge Gallery called Motion Makes Us Sleep, through April 11).

One piece in Zounds is "Sleeping Beauty with Pins" (2001) by Judith Brotman. The work is an altered children's book relating the fairy tale of sleeping beauty. The book is open to the part of the story in which Aurora pricks her finger on the spinning wheel. Both pages of the open book have pins stuck vertically on the pages. It seemed to suggest the bed of nails that some use as an agent in meditation or prayer. Prince Charming enters the scene "armed with the Sword of Truth, the Shield of Virtue, and the Strength of True Love."

Teresa Mucha's two drawings, "Blossoms of the Flesh" (1999) and "Blood of the Bloom" (1999) are two classical portraits of women. Curtains surround the figures, making it appear as though the women are on a stage. Mucha deviates from the classical, substituting simple portraits of women with somewhat disturbing faces. In "Blossoms," a large flower blooms where the nose would normally be, obscuring the woman's features. There is a diamond-shaped gap in the woman's neck, from which vines extend. In "Blood," another flower covers the woman's face, and a series of wounds on the neck are reminiscent of the slit in the side of Jesus caused by a soldier's spear before he was crucified. Mucha's work suggests many things, including the transitory nature of the physical body, as well as the concept of "dust returning to dust."

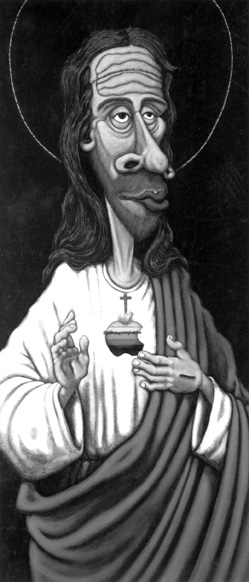

Greg Porcaro's three pieces have distorted figures, as well as a dark sense of humor running through them. In "Deus ex Machina" or "A God (played by Frangi) Out of the Machine," Porcaro paints a distorted Jesus with a large nose and pouty mouth as well as putty-like skin. A wooden tabernacle frames Jesus. On both his chest and the top of the tabernacle, instead of the sacred heart, there is an Apple logo topped with flames and encircled by a crown of thorns. In "I'm Falling (Apart) ... Who Will Save Me? (2001)," there are two hands in the heavens, as well as a figure falling into a pit. The two hands hold on to what appears to be the man's intestines, emerging from a gaping wound in his stomach, although the intestines are depicted in such a way as to resemble a rosary.

Other work in Zounds includes "Michael," by Debra Tolchinsky. The work is a blurred print of a nude, androgynous figure that resembles Michael Jackson, which leaves the viewer to come to his or her own conclusions about wounding in relation to the physically altered pop star. Also shown is a Henry Darger piece, titled "Sacred Heart," which is a watercolor depiction of the sacred heart topped by a cross. There are also two pieces by Brian Dettmer called "Scoop" (2002) and "Alternate Route to Knowledge" (2001). Both "Scoop," a carved set of encyclopedias, and "Alternate Routes" are sets of books with the centers bored out of them.

Curated by Jeremy Biles, a PhD candidate at the University of Chicago Divinity School, Zounds aims to "examine the relationship between wounding and the sacred in contemporary art and society." The images, in addition to wounds, often employ Christian/Catholic icons, and suggest the fragility of the human body with its cuts, slits, blood, and other physical flaws.

In an interesting curatorial decision, there were no individual labels for the artist or title of the pieces. Instead, a price sheet/gallery guide with all relevant information was provided instead, which proved confusing at times, especially when there were multiple works listed for one artist. Additionally, there were no artist statements, due perhaps to the group show format, but it would have been nice to have a little tidbit of insight from the artists themselves on the motivations and inspirations for their work.

The work itself is sometimes disturbing, often humorous, and, the curator hopes, an agent of joining. He writes, "... The wounds that cut are also the ties that bind, and a showing of wounds ... that connects us to each other. It may be, then, that exhibiting wounds is itself an act of religion, reconnecting, and that the wounds thus shown become, in some sense, divine wounds."