Joining the

Games

Leon Golub on Art and War

|

I’m

showing how the head of the artist is situated in the world, how the world

is sending him impulses, where he or she is going, or not going. |

|

Leon Golub believes that the epitome of urban art can be found in Greco-Roman classicism. For Golub, it seems, the curve of an Apollonian sculpture has more to say about politics and the struggle to survive than any modern abstraction. Yet he deals fiercely with the canvas — he cuts and scrapes at the subjects of his work rather than caress their heroicism or polish their Davidian grace. Since his tutelage at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Leon Golub has now seen hundreds upon thousands of images: mass graves, napalm lesions, nuclear meltdowns, tortured, flayed, and beaten men, land mine victims — optical nightmares that refuse to allow his brush to rest. Formally, his faculty is as monumental as his terror is intimate; his figures yield entirely to the tactility of their flesh and the distortions of Golub’s nervous mind. It is perhaps too easy to determine the best of Golub’s work: his most violent and figurative paintings. The bleeding fibers of these monstrosities smack us down with a libidinal fervor. Craving this punch we cannot help but be indicted in our orking in that vein with some 30 ink works on canvas showing with some kind of language. These pieces are small, about 2.5 to three feet. Using language like this is an attempt to get an intimate aspect in the work, because in a way there is a physical closeness, a susceptibility where the victimizer is ultimately up close. This is different than the own appetite for violence because we need those images that can put our consciousness up to the fight. It is in the mental alleyways where we stiffen our backs and ready our fists that we can later scrawl our name across, be it with paint or blood. So it is for Golub, both gladiator and crucified lion, that our modern landscape becomes a Colosseum of spectator sports, fascinating and horrific.

Can you talk of your recent work, what you are working on now, especially in terms of its interest in contemporary events?

Basically my work deals with politics. I’m still working in that vein

with some 30 ink works on canvas showing with some kind of language. These pieces

are small, about 2.5 to three feet. Using language like this is an attempt to

get an intimate aspect in the work, because in a way there is a physical closeness,

a susceptibility where the victimizer is ultimately up close. This is different

than the Mercenary paintings, where there was a distance, where there is some

foreboding but not the same kind of action as with these smaller works. That’s

my notion of how struggles have gone on in Kosovo [and] Rwanda, looking for

a casual, everyday look, not so much the formal aspects of war, combat, covert

actions, etc.

At the same time I am working on larger paintings; my last painting was around

8 feet by 8 feet, showing a male lion covering most of the space with its head

turned in a snarl. Underneath its paws are two skulls taken from photos of lion

skulls. He has a gold sash across his waist and a green earring, so he isn’t

a typical lion! “INEVITABILE FATVM” (inevitable fate) is printed

above and means “an epistemology of the skull,” a little pedantic,

eh? But I try to give a twist. Underneath this phrase is written “in the

pink.” So I’m trying to take the negative and throw “in the

pink.” So that’s what the painting is like. It deals ferociously

with how people handle other people, torturing and killing, but also taking

a philosophical look at survival. I’m sort of political, sort of metaphysical,

sort of smartass. I’m attempting to be young ... it’s a lost cause!

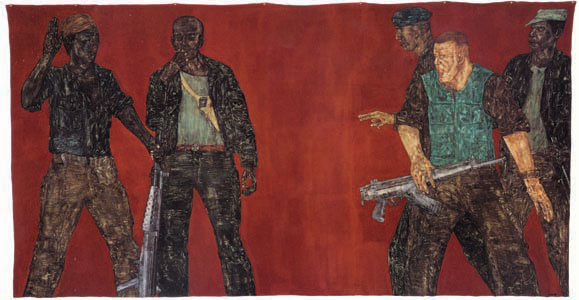

Mercenaries

IV, 1980

Mercenaries

IV, 1980

Could you say something about the impact of media and information overload on the making of your art?

I think of information as encompassing almost everything today; it drives us in every which direction, atomized and totalizing, from Internet, to television, to photography, etc. The visual is so important today; this is a more visual period of time than ever. These are the means we have to enter society; artists interrupt situations and work around the edges of things; we are working with how information enters the scene, how we are made up of information. If we look at the variety of art made today it’s more varied than it’s ever been.

So you believe that your work is loaded with as much information?

Depends on how information is inferred. If I was showing a mercenary smiling, making a gesture, then I’m showing how mercenaries function, where this guy is coming from, maybe how he’s coming from the background of American support for the contras. You ask yourself, “What’s he wearing? Why the hell is he smiling?” I am showing the assumptions of men, but I’m also showing how men pal around, how men under stress relax. I’m showing how the head of the artist is situated in the world, how the world is sending him impulses, where he or she is going, or not going.

I see in your work an intimately combative relationship with the alien, in terms of the foreigner and the alien parts of the self. Is this a positive relationship for you?

Aggression and hostility are never necessarily positive, positive if you are protecting yourself. It’s not positive if it’s solely male aggression. My work has a lot of that in it, and I think there is a lot of that in the world. So in that sense I think of myself as a realist; it’s real in that it’s out there happening and also happening inside you. You asked about aliens. I’ve thought of that a lot. I’ve done these pictures of sphinxes, part human, part lion. We also have cyborgs, where the human is transformed into a kind of future creature. Alien in the sense that once you cross a border you are in another territory. Aliens are border creatures. They are straddling the border, culturally intermixed, and they often offer the unexpected.

Can this “enemy within” that seems to drive your works perhaps also be bound up with your conflict with society?

I feel relatively sane, but I think we all have forces of energy that move through us, that we call upon to simply walk on the street. The violence that I portray often has residence in the violence in the streets in the world. There is terror in me; sure I’m terrorized, but I think we are vulnerable to remarks and physical threats. This vulnerability is physical, mental, and [thus] we set up protective systems. Often we use art as a means of avoiding contact; some people look for violence as a contact and others are very strongly repelled by it. The world is right in our face now; if something happens we immediately get a version of it within a half hour. So the world is entirely on top of us in this respect; we take protective action or join up with a bodily energy that makes us think we are ‘in the pink.” The world is going to affect you, move through you.

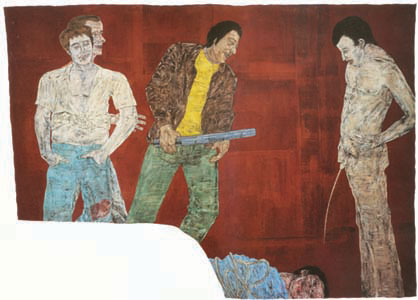

Riot I, 1983

Riot I, 1983

Why does your work mostly concern itself with extreme states of mind, like extreme hatred, anger, and vulnerability?

That’s the way I am. But I think there are a lot of subtleties in this. If you are a perennial optimist, pessimist, [it] doesn’t mean you can’t be subtle or contradictory.

Why are there no background figures in your work?

Very rarely there are. I have a tendency to push things forwards, facing out, on the front plane, in your space, in your face. I don’t like recessions, where things disappear; one should encounter the front plane physically.

Your art has been called Classical on many accounts, but I find it almost pre-Grecian in that it takes into account the raw force that brought to bear civilization. Can the Classical be both refined and primeval at once?

I’ve had Classical influences in the ’50s and ’60s where I’ve taken images from Classical art, but I do them in my technique, which is rougher. I take the Greek sculpture’s harmony and I try to rough it up. I like very early and very late Greek art, and I like the colossal stance of Roman art. Their art is often like their buildings, great intimate art, wonderful genre scenes, things depicting nature; it had a lot of range to it. I like to think of it as urban art. Roman art was very public, right there, like the emperors and the wars, great psychological focusing on faces and gestures, so there was strong portraiture, public and political art. Art is very public these days. A huge encompassing of an enormous range of possibilities.

What have been your confrontations with style as you struggle with your confrontations with society?

You have to find a way to make what you want to make, getting it into form. Often you have to use a deviant path. Avoid the typical — whatever it is! How have you arrived at it? Styles are ideas into form. We insist that the ideas and the form are the same. Artists often are stylists, but for most artists the style is the bones of what you are doing.

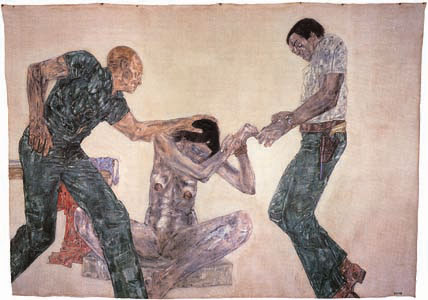

Interrogation

III, 1981

Interrogation

III, 1981

In the late ’40s, most of the men at the Art Institute were World War II veterans. There is less of a physical presence of war at the school now. How do you think this could change the kinds of art produced?

Your generation has enough to struggle with. You have very serious problems to deal with in style and form, how you make your work evident to the world. The questions artists ask themselves are usually the same. Are you comfortable in the world? How do artists function now that is different from 20-30 years ago? Who among artists can you really respect? Are you concerned about war in Iraq? You can either work with this kind of problem in your art or outside of your art.

During the Vietnam War protests we had exhibitions, collages of dozens of pieces where some showed political tension, others were abstractions, but all felt it was their contribution to the struggle. In a sense the job of your generation is the same as every other generation, including the cave artists: how can you uncover what you need to do! Do people around you stand by your work? Are they hostile to it? Do you stand together as a group or are you isolated? How do you function in the art/world nexus?

You are at a special school in a special country; different for example than trying to be an artist in Mexico. You are situated within the world you’ve been given. Do you want to break with that? How to be objective about your work: am I on the right path? Should I change, be different? Ultimately it’s your decision to change your style of working; you might choose to quit art altogether and stand on a soapbox and shout instead.

Images courtesy of Chicago Cultural Center