| |

|

|

|

Interview With New York Painter Hillary Harkness |

Laura Smith |

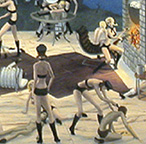

New York artist, Hilary Harkness, paints finely detailed scenes of off-duty sailors in submarine sleeping quarters, lederhosen-clad art thieves in a Swiss chalet, and Gallic warriors, among other things, engaging in what you might expect them to engage in during their down time--sex, mischief, self-adoration, drive-thru fetus implantation ... oh, wait. Of course, these are not conventional warriors, and Harkness is not mining the old trope, the war of the sexes. Despite an occasional penis, the phallic-shaped chute or mast, even a reference to the Pope of modernist machismo, Picasso, every figure in her narrative is a woman, and a busty one at that.

New York artist, Hilary Harkness, paints finely detailed scenes of off-duty sailors in submarine sleeping quarters, lederhosen-clad art thieves in a Swiss chalet, and Gallic warriors, among other things, engaging in what you might expect them to engage in during their down time--sex, mischief, self-adoration, drive-thru fetus implantation ... oh, wait. Of course, these are not conventional warriors, and Harkness is not mining the old trope, the war of the sexes. Despite an occasional penis, the phallic-shaped chute or mast, even a reference to the Pope of modernist machismo, Picasso, every figure in her narrative is a woman, and a busty one at that.

It is a rewriting of sorts in which "beautiful young things" can fudge the boundaries that they have historically been assigned such as virgin or whore, mother or mistress; that, or entirely supplant their male predecessors. She can wield a machine gun, impregnate herself, play nefariously erotic games with her shipmates, all without mussing up her hair. Like Irina Dunn said in 1970, "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle." And who needs a bicycle at sea? Still, these worlds are not without consequence. Granted, in fantasy, moral codes can be easily subverted or overcome without much trouble, but in this fantasy, women seem to be paying a price for their amorality. What have they lost in exchange for "having it all?" Well for one, they are completely devoid of personality or empathy, think Veronica Lake � la Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

This approach has served Harkness well. She is currently represented by the Mary Boone Gallery in New York City, and both critics and collectors are enamored with her work. Jerry Saltz, critic for The Village Voice, wrote about her figures, "Whatever they're involved in, they ooze a bitchy demonic kinkiness, which makes looking at these paintings slippery fun." He goes on to salute her paintings' ambiguity, moral transgressions and oft-perceived, though incorrectly so, lack of concern for feminist politics, and he is not the only one. I wonder why? Harkness' second solo exhibition in New York opened last spring at Mary Boone, featuring two of her most recent paintings, "Crossing the Equator" (2003) and "Matterhorn" (2003-04), both elaborating upon in her girl-world myth, and both even more intricately painted. I spoke recently with Harkness, in a series of conversations about her work and its reception, and learned that the truth is ever more ambiguous than it seems. The following is an excerpt from that conversation.

This approach has served Harkness well. She is currently represented by the Mary Boone Gallery in New York City, and both critics and collectors are enamored with her work. Jerry Saltz, critic for The Village Voice, wrote about her figures, "Whatever they're involved in, they ooze a bitchy demonic kinkiness, which makes looking at these paintings slippery fun." He goes on to salute her paintings' ambiguity, moral transgressions and oft-perceived, though incorrectly so, lack of concern for feminist politics, and he is not the only one. I wonder why? Harkness' second solo exhibition in New York opened last spring at Mary Boone, featuring two of her most recent paintings, "Crossing the Equator" (2003) and "Matterhorn" (2003-04), both elaborating upon in her girl-world myth, and both even more intricately painted. I spoke recently with Harkness, in a series of conversations about her work and its reception, and learned that the truth is ever more ambiguous than it seems. The following is an excerpt from that conversation.

Hilary Harkness: As an introduction, I think that many paintings, both historical and contemporary are really quite boring. I like painting, I enjoy the activity, and, as something I am going to spend most of my time doing, I figure I might as well try to make them interesting.

Laura Smith: I guess I'm mainly trying to get at the question of overt representations of female sexuality and violence and why you paint these things. In your recent paintings, specifically "Crossing the Equator" and "Matterhorn," what's going on in these and how do they fit, or not, within this world you've created?

HH: I would say it's more about sex and power, not violence. These two things have a simultaneously immediate yet hidden appeal. They draw you in. My paintings are about these, but also much more. I use them to pull the viewer in; from there, I explore the issues in more detail, sometimes in twists-and-turns and sometimes to the point of their own banality. I also think the manner in which I paint them is important: slow, small, detailed. This allows me to investigate these issues of sex and power in a more detailed, articulated, and maybe thoughtful manner. I hope to infuse these issues with meanings deeper and more idiosyncratic than typically found in the culture at large. I cannot separate how I paint from what I paint, the paintings are not just about one or the other, and hopefully the how and what contrast and combine in a way that creates something interesting, charged.

HH: I would say it's more about sex and power, not violence. These two things have a simultaneously immediate yet hidden appeal. They draw you in. My paintings are about these, but also much more. I use them to pull the viewer in; from there, I explore the issues in more detail, sometimes in twists-and-turns and sometimes to the point of their own banality. I also think the manner in which I paint them is important: slow, small, detailed. This allows me to investigate these issues of sex and power in a more detailed, articulated, and maybe thoughtful manner. I hope to infuse these issues with meanings deeper and more idiosyncratic than typically found in the culture at large. I cannot separate how I paint from what I paint, the paintings are not just about one or the other, and hopefully the how and what contrast and combine in a way that creates something interesting, charged.

LS: Why have you chosen to depict these worlds in which women, and only women, perform actions historically and stereotypically performed by men?

HH: It is a process of displacement and replacement. I think this makes for worlds more interesting and charged, where the ideas of gender, sex, violence, and history blur. Also, I am actually very much interested in the worlds I depict, it just so happens they were, historically, ones dominated by men. I'm not interested in simply depicting these worlds, but, rather, in really creating them. Re-inhabiting them in this way helps me do so, and in a personally compelling manner.

LS: Why associate sex and feminity (these sexy, scantily-clad ladies) with violent acts--as soldiers, warriors?

HH: I think it's more power than violence. At the same time, I question notions of power since so much of the violence in war was caused by incompetent bumbling, friendly fire, bad design of weapons and vehicles, and poor planning.

LS: Are you interested in redefining these roles, gender roles, i.e., reconsidering history and/or literature (fantasy/fairy tales, etc.) with an all-female cast? In other words, do you care to take on gender politics, or make a statement about this?

HH: If I have an interest in redefining or reconsidering it is not in any obvious terms, I will let the critics do that. While I do find it interesting, I see it also very much as a starting point, a displacement that allows me to both examine yet imagine, re-create yet create.

LS: Your work has been associated with a contemporary interest in re-imagining fairytales, creating new myths or revealing the more insidious underbelly of fairytales. Do you care to participate in that?

HH: I personally am more interested in creating worlds rather than making comments on others but I don't have a problem if others want to see that in the work.

LS: You also seem to be interested in sophisticated formal issues (interesting overlapping of body parts, a grid-like layout). Do these formal decisions play at all into the story you're trying to tell, and how?

HH: Certain formal issues are of great importance to me as a painter. I am equally interested in painting itself as I am in what I paint about. As such, the two are intertwined. Just like I try to make work that is complex, articulated, interesting, and charged in its content, likewise I try to do so formally, visually, in paint.

HH: Certain formal issues are of great importance to me as a painter. I am equally interested in painting itself as I am in what I paint about. As such, the two are intertwined. Just like I try to make work that is complex, articulated, interesting, and charged in its content, likewise I try to do so formally, visually, in paint.

LS: Why do you work in the medium you've chosen, in a small scale, with great attention to detail and tightly rendered, realistic forms? Does it have anything to do with these worlds you've envisioned?

HH: I am interested in painting and in the manner in which I paint, it is what I do as my practice. With my painting I try to really create complex worlds in which I can further investigate in an articulated manner--both in terms of the content and in terms of painting itself. To create these worlds, I find attention to detail is important. The world is known in its detail.

November 2004