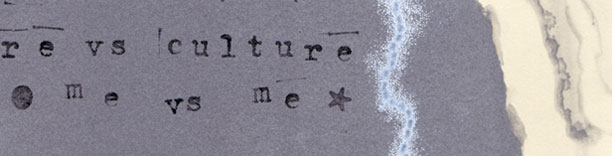

Dorota Biczel Nelson, Untitled, 2008 (detail) monotype print with rubber stamp, 24 x 8 in.

Commute: Commune

Living and belonging between two cities

I haven't made an obvious choice. People tend to be deeply surprised when they hear I live in Milwaukee and study in Chicago.

"Milwaukee? How far is it?"

"Not that far, 80 miles north."

"So, how long does it take you to get to Chicago?"

"Oh, two hours or so. It really isn't that bad." My response is frequently met with uncomfortable laughter, as if what I undertook was a trek to the North Pole twice a week. It really doesn't matter that a ride to Rogers Park takes an hour. Not only do I live in a different zip code, but in my address the zip code is preceded by two completely different letters. I think that, to some, these two letters hint at an unspoken gap between a cosmopolitan Chicago and a "hick" town up North. I also feel irreversibly branded as an alien, a tag I cannot seem to shake off.

Still, I feel I have to explain myself. So here I expunge myself in writing, not to stop people asking because if you really care to know, I'll be happy to tell you how great Milwaukee is but in order to reflect on how and where we choose to live our lives as artists, curators, writers, and other "creative" types, why we might want to travel between communities, and what it means to cross a border every day, no matter how uncomfortable and precarious the passage might be.

There are many good reasons to commute, and I am hardly the sole desperado traveling the route. Actually, as many sociologists and globalization specialists have observed, it seems that the vast majority of humanity is on the move these days. Zygmunt Bauman said that in the liquid modernity we have to adjust our life strategies and make them appropriately malleable. My routine journey has revealed to me a rich variety of fellow passengers. While I watch them, I am secretly guessing their dreams, and wondering what propels them into motion. Sometimes I even dare to ask.

COMMUTERS, A BRIEF TAXONOMY:

Traveling north to south:

a) Morning: corporate executives and management-level professionals, their bluetooths blinking feverishly, making urgent calls at 6 a.m.; little towns between Milwaukee and Chicago are good for low property taxes and raising kids…

b) Mid-morning: stay-at-home moms en route to the Magnificent Mile (or the opera, if it's a mid-day train); they too have a fashionista in them, they too want their girls' day out. You should hear them giggle.

Traveling south to north:

a) Morning: gardeners, nannies, house cleaners on their way to the North Shore McMansions; mostly Latino, or sometimes Polish, they too think of their children.

b) Late night: people who work in the service industry in Chicago bartenders, cooks, security guards, marines after the day on the town…

When I pondered the question "to move or not to move?" the dilemma was both simple and infinitely complex. Is the grass greener on the other side? Are my chances of professional success greater in a bigger city? How much better will an American degree be than my Polish one? Finally, do I want to leave behind what I gained in the past five years? The last question brought to mind the ruminations of the critic Dave Hickey on the difference between the "scene" and the "looky-loos;" that is, between participants, who are in and understand what's going on, and spectators, who just want to be hip.

I ended up in Milwaukee at the end of a very long trans-Atlantic commute. Slowly and to my own surprise, I witnessed the scene materialize around me. "Scenes," after all, are not just a privilege of New York, Los Angeles or Chicago.

The local scene in Milwaukee doesn't have a metropolitan allure, but nonetheless we're forthrightly committed to what we're doing. Do I just drop this for a potential metropolitan bliss and shorter train journeys?

Because commuting seems to be a part of my genetic make-up, the decision was finally made. I first began commuting, back in Poland, when I started high school. My mother strongly believed that we had to leave our hopeless little industrial town if we wanted to get anywhere in life, so, at the age of fifteen I started taking a train to Warsaw, to a school that would provide me with a "proper" education, and peers with respectable lofty aspirations. As it turned out, I did not trade my old friends for the savvy city dwellers. I soon discovered that instead of belonging to both places simultaneously, I was neither fully here nor there. The last train always needed to be caught. It was the only time in my life when I felt like Cinderella, just because I had to leave as soon as the clock struck midnight. I made my best friends on the train.

Commuting shares many similarities with living in the borderland. The borderland is a nebulous area, a fertile ground of cohabitation and cultural exchange, albeit not trouble-free. My idea of the borderland was shaped in relation to the verge of Central Europe. When I was growing up, in the 1980s and 1990s, Poland's aspiration to be "European" was notoriously under international suspicion, due to communist allegiance of our government. However, Poland was also thought to have an advantage over Westerners: we could claim to understand Russia and have an insight into the tormented, irrational Slavic soul.

In his essay "Where is Europe?" writer Orhan Pamuk observes that the position on the periphery gives one an impression of having somehow a clearer, more faithful picture and, as a result, of superior knowledge. Is it just an illusion? Pamuk does not shatter this myth. As I juggle my life between different communities, I strive to have a good insight of both. In the most optimistic scenario, those on the borderland may hope to experience the best of two, or more, worlds.